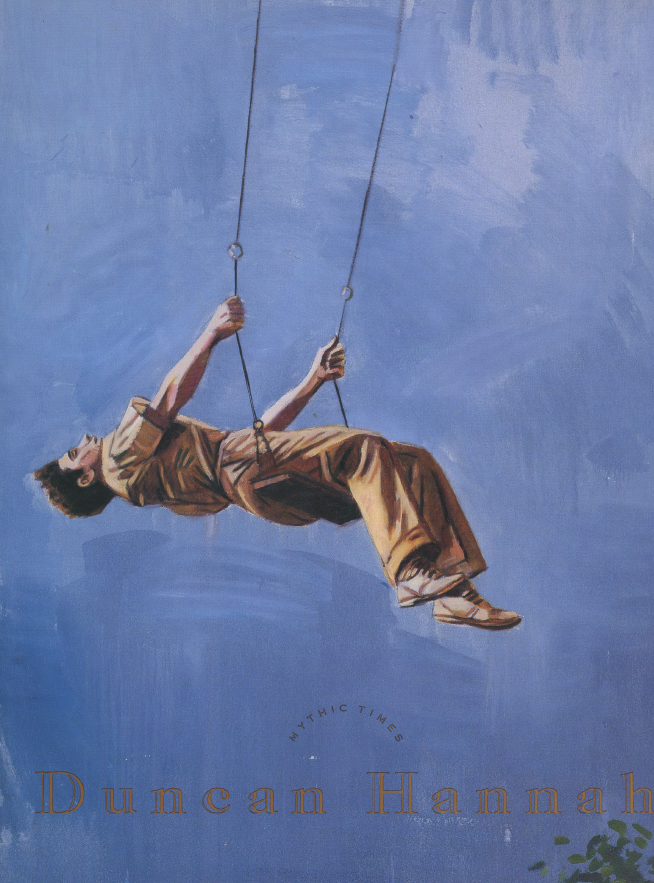

Duncan Hannah: Mythic Times

April 24 - May 27, 1990

Duncan Hannah: Mythic Times presents 33 paintings created by the artist between 1977 and 1990. An ancillary exhibition of paintings and prints by such notable artists as Edward Hopper, Albert Pinkham Ryder, and Ralph Edward Blakelock provides a unique opportunity to view works by important artists who have influenced Hannah over the years.

Duncan Hannah has gained a well-deserved reputation as a painter who has consistently followed his own artistic direction while wisely and selectively borrowing from styles and subjects of the past. Born in Minneapolis in 1952 and educated at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design and at the Parsons School of Design, Hannah has developed a manner of painting which carefully balances narrative and figurative elements with a love for loose yet descriptive brushwork, highly expressive color and finely tuned composition. Stylistically, these paintings closely recall works by painters such as Paul Cezanne, Andre Derain, and Paul Gauguin. The attitude they project, however, more accurately brings to mind Edward Hopper, the American artist whose paintings of solitary figures, streets and buildings still speak to us of a "psychology of isolation." In many cases, Hannah's paintings indulge art-historical fantasies, allowing us to answer questions like "what if Cezanne were mixed with Hopper, or Balthus with Derain?" In Mythic Times (1985), the title painting of the exhibition, an adolescent boy stands in front of a scene which, at a glance looks common or even bland, but actually contains the potential elements of a heroic tale. Like nearly all of Hannah's paintings, Mythic Times is tinged with nostalgia, looking like an innocent, pastoral scene from the landscape of the past. The boy's attention is turned from us and is given completely over to the book he holds, which might well be Homer's Odyssey, with the sea, the modest boat, the vast threatening sky and the inviting, warm-colored house suggesting various elements of that story. Travel is a recurring theme in Hannah's work, manifesting itself literally in images of ships, roadways, cars and trains, and in a figurative or psychic sense in the dreamy, pensive attitudes of his figures. In a Duncan Hannah painting, the action is stopped, but the scene has not changed yet—something is pending and the next act is always about to happen. The artist supplies the skeleton of a narrative, and the viewer is invited to build the body of a story around those bones, and to animate Hannah's mysterious, self-absorbed figures. Duncan Hannah's paintings are full of ordinary objects, scenes, and figures which are painted with reference to familiar 19th and 20th century styles. The post-impressionism of Cezanne and Gauguin; the full-blown color of Bonnard; the directness and near abstraction of Edward Hopper—all of these influences, as formidable as they might seem, are skillfully interwoven in Hannah's paintings, which are always beautiful, but never merely beautiful. Although his subjects are always identifiable, Hannah is not only concerned with an exact replication of things; he is interested both in producing a version of reality in paint that is visually and formally interesting, and also in bringing viewers to a point of emotional empathy with his subjects and their environments. In the painting Solitaire (1983), Hannah presents us with an understated version of what could be an existential dilemma, where a game of random draws is the most meaningful activity, carried out in front of an expressionless void which could very well be a New York School geometric abstraction. Judging from her hairstyle, the woman card player looks oddly dated, and everywhere in Hannah's work, people, clothing, cars, and buildings appear to be typical of an earlier time, perhaps the 1940s or 50s. As Carter Ratcliff said in a 1985 catalogue essay, "Hannah feels that a car or shoe from the time of his youth is more like a car or a shoe than its contemporary counterpart could ever be."

It is obvious that archetypal images function better than specific places or contemporary figures in Hannah's paintings because they allow for the creation of an atmosphere, a general circumstance to which all viewers can easily relate. In Swing (1987), Hannah employs a perspective which renders the swinging boy only loosely connected to the earth, and thus succeeds in emphasizing the reverie and abandon of such a moment, one all of us have experienced before. The fact that the self-absorbed figures in most of Hannah's paintings are young and nearing or in puberty, identifies him with Balthus, whose paintings of the 1940s and 50s often depicted young girls in dreamy, distracted states. In Hannah's work, states of mind are as obvious as mimetic qualities and formal structures; despite their sometimes common or nondescript appearance, these paintings exude a wealth of psychological content. While he often utilizes past styles, Hannah is not interested in Fauvism or post-impressionist abstraction for their own sakes, but consistently pushes style together with moody and portentous narrative. But to call Hannah a narrative painter, or only a narrative painter, seems unfair both to him and to painting's long history of storytelling. Everywhere in these paintings, stories are suggested and clues of time, place, mood, and event are given generously, but never absolutely. The viewer's own chronological and emotional history is always the missing element in Hannah's narratives. Color ranges from local, to heightened, to subdued; form is built and simplified with Cezanne-like strokes, dashes, and patches of paint; flat and nearly abstract passages mingle with those producing depth and modeling. In the midst of all this painterly activity, Hannah realizes unique worlds for his archetypal figures, with which we can all, for one reason or another, identify and empathize. Although many artists have influenced Hannah, these paintings are uniquely his—the use of past styles is not only an ironic "quotation," as some critics insist. Instead, Hannah recasts some almost dangerously overused (and by now even trite) styles and functions of painting to produce a new and distinct voice—one clear enough and mysterious enough to appeal to both lovers of "old-fashioned" narrative, romantic art, and those expecting a "new" art of speculation and detached commentary.

Publication

Exhibition Documentation

Events & Programming

Exhibition reception

April 24

7:00 p.m. - 9:00 p.m.

Exhibition Information

Exhibition Tour

University Galleries

Illinois State University

Normal, Illinois

April 25 - May 27, 1990

Moody Gallery

of Art

University of Alabama

Tuscaloosa, Alabama

August 24 - September 30, 1990